Pigeon-Vision

The view from the Dialectogram

Whether running with their crew or playing their own angle, Rattus Volaticus carves out its territory from the kerbs and cornices with a keen awareness of crumb, kebab and chip spillages. The pigeon is down, and it is dirty. It is street-wise, it is, as the theorist Michel de Certeau would say, ‘clasped to the street’. But it also flies, which means our pigeon also takes the bird’s eye view of that same street.

In that, it beats us humans hands down. There is evidence that prehistoric shamans , through substance-assisted visions conceived of the bird’s eye view back in the age of the stone hand axe. But for most, it was something they could imagine but never share, and it has remained the viewpoint of the privileged, the powerful, the elevated. As geographer Hayden Lorimer remarked to me, when we think of the bird’s-eye view, we imagine great migratory birds, the truly high-flyers who do not deign to land until they’re good and done – the swallows, the swifts or geese. We do not imagine pigeons, the rat with wings, the flyer of low birth and lineage, irredeemably a bird of dirt, asphalt, muck and discarded things.

Back in 2009 I ‘invented’ something called a ‘dialectogram’. I made the name up by conflating diagram with dialect; so diagram + dialect = dialectogram. Both words incorporate the Greek ‘dia’, meaning across, through or apart – definitions I could squeeze and manipulate as I needed. But why incorporate ‘dialect’ at all? It is first of all, a linguistic metaphor. If we see drawing as a language of sorts – the different marks, lines and gestures we make in a drawing are as particular as speech. And like spoken or written language, drawing has its accents and variants. It can be formal – or posh – like the mannered drawing style of the art academy or the precise ‘jargon’ of technical drawings and architectural plans. It can be as down and dirty as a sketch or have the qualities of a demotic or dialect in the form of graffiti, folk or naïve art, or be as peculiar and individual as a pencilled portrait or doodle. The word ‘dialect’ as I use it (idiolect may actually be better), represents a whole range of ways in which language can vary beyond official or ‘proper’ usage.

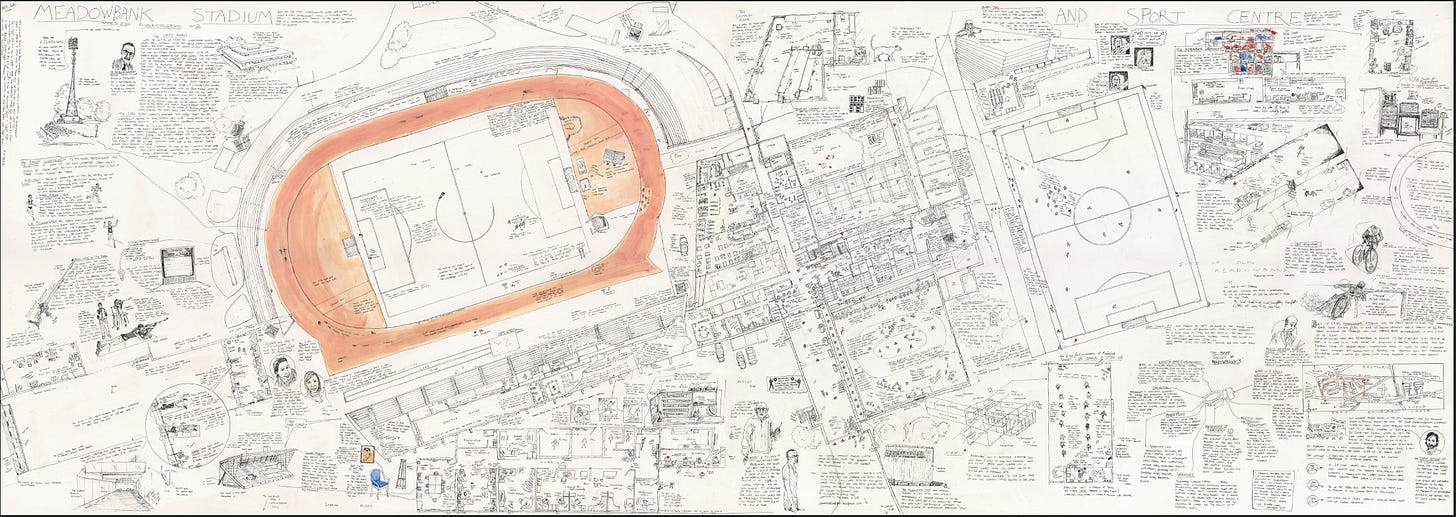

The images that result from this, whether it’s the series of five I made at the iconic Red Road Flats in Glasgow, the Piershill Community Health Flat, the Claypits Nature Reserve, Clydebank Library or the Barrowland Ballroom reflect what you might call the pigeon’s-eye view. We might see Meadowbank Stadium (home to the 1970 and 1986 Commonwealth Games in Scotland) from above, but the majority of what it shows you is based on knowledge of what is happening in its corridors, halls and pitches. Like the women of Piershill Square West, less than a mile away, who kept their eye on their community from the flat on the corner, the pigeon-eyed dialectogram gets to know its turf intimately – who is who, what is what, where it all happens – while keeping in mind how it all fits together.

This is the opposite of what we tend to see in modern maps, where this kind of local knowledge is rarely included or even seen as relevant. These documents clear the strolling, loitering, perambulating pedestrians away from streets that only exist because such people need to move from place to place. Put another way, the map tends to articulate the drawing language of the powerful, not particularly interested in communicating low-level experience as say, the sketch maps mentioned in Tim Ingold’s ‘A Brief History of Lines’

‘…the lines on the sketch map are formed through the gestural re-enactment of journeys actually made, to and from places that are already known for their histories of previous comings and goings. ‘

So you have to be careful when taking the bird’s-eye view. Back in the ‘90s I read ‘What I Hate about the News’ (1994) an essay by the poet Tom Leonard on the first Gulf War which stuck with me long after. Glasgow’s most curmudgeonly poet (primus inter pares amid some tough competition, by the way) describes the spectacular news footage we have become horrifically inured to as media spectacle -although the current horrors of Gaza might suggest that Western indolence has reached its limits. Here Leonard recalls the experience of watching guided missiles being dropped on Kuwait, far enough below to look pretty much like a map:

It's one thing to have wide-angle spectaculars of twelve-rockets-at-a-time whooshing upwards into a dark desert sky, patriotic flag somewhere on screen; it’s another to have wide-angle spectaculars of what happens to the conscripts on whom the over eight thousand disintegrating “bomblets” fall from each salvo.

I think it is no coincidence that the overwhelming public disgust at what is currently happening in Gaza, despite the sophisticated media management of the issue is due in no small part to the power of social media to capture and distribute footage from ground level, each video another bit of grit on the lens and in the eye.

It's a long way from the Gulf to Glasgow’s east end where Backcauseway, the first ever dialectogram came into being. But when I made those first tentative marks I was indeed thinking about Leonard’s words – and increasingly of the opinion that they spoke not just to the specifics of the Gulf War, but in a more expansive sense, established some core principles of how optics shape our thinking. It is not dissimilar to Alasdair Gray’s thoughts, via Duncan Thaw, on the potential distortive effects of viewpoints he put forward in Lanark, namely, that a sea-shell is only a pretty, delicate thing if you don’t happen to live in it.

Frequently, top-down views obscure local culture; they observe – and describe – life, totalise it (to quote Michel de Certeau) but do not participate in, or take any stake in it. It is rendered, as Ingold (a wonderfully strange bedfellow to Leonard and Gray to be sure) would put it, as mere pattern, as he describes the experience of looking at a local forest from the top of Mither Tap, a peak in Bennachie, Aberdeenshire:

‘To see the wood, it seems, you have to get out from among the trees and take a long view from a bare hilltop. Or even from the air. Seen thus from afar the wood appears to be laid like a mosaic over the contoured surface of the land.’

The mosaic view – what Ingold calls the ‘pictorialisation’ of the landscape, turns the organic, breathing, pulsing tangle of trees into a mere idea of such – and I would argue, once you turn actual things into ideas, it makes it easier to supplant them with others, to realise the masterplans of politicians, planners and architects (or, let’s be honest, dialectographers). This is not in itself ‘wrong’. Sometimes you have to reimagine the real in order to best deal with it. But if we’re not careful, such a process view can make us callous, overly-hygenic in our thinking, all too happy to clear away what is inconvenient or messy. In architecture lines propose, they represent to a greater or lesser degree, an exercise of authority (actual or intended) over a given space: the power to build a wall, to hem in, to prevent people moving freely from one point to another – to tell them what the landscape is.

*

The announcement in 2008 that Glasgow would host the 2014 Commonwealth Games and that, as a result, an ambitious programme of regeneration would change the east end dovetailed with plans for a major extension to the M74 Motorway and the ambitious strategies of Clyde Gateway, the partnership that oversaw much of the Games’ legacy commitments in Dalmarnock, Parkhead and Bridgeton on the north side of the river Clyde, and Rutherglen and Shawfield to the south. It was these changes that set the literal groundwork for dialectograms, as much a legacy of the 2014 Games as the Emirates Arena, the Sir Chris Hoy Velodrome or the dancing Tunnock’s Teacakes from the Opening Ceremony.

The plans were ambitious; the much-neglected district of Dalmarnock, home to Baltic Street Adventure Playground, would be home to the new stadia. The Clyde Gateway vowed to bring jobs to the area and build significant new residential properties, sports and leisure facilities, all grist to a ‘vibrant, new city district’. This led to a process of land procurement through compulsory purchase orders and the subsequent clearance of existing communities within Dalmarnock – although much of the official images and rhetoric acted as if there were none. And fair enough, when viewed from an architect’s masterplan, high up where the swallows flew, it’s not as if they were visible.

I live in the east end, as did a sizeable chunk of family and friends who formed those apparently non-existent communities sitting in the path of this redevelopment. Cases of resistance and disagreement were already coming to light: for instance, photographer and filmmaker Chris Leslie documented the long and bitter stand-off against Glasgow City Council by local homeowner Margaret Jaconelli, and I teamed up with Chris and Alison Irvine a few years later to follow this up and examine the changes to Dalmarnock that came about once the tenements fell. And yet there was also much smoothing over: Stephen Bennet’s otherwise excellent series on the redevelopment of Dalmarnock left out the large community of Travelling Showpeople whose yards are located in the area (even in its aerial shots which, given how numerous these yards are, was quite a feat in itself). Dalmarnock was put at the centre of a paradoxical narrative that, on the one hand, indicated it was deserted, yet on the other, emphasised how much ‘existing’ communities would benefit alongside the new.

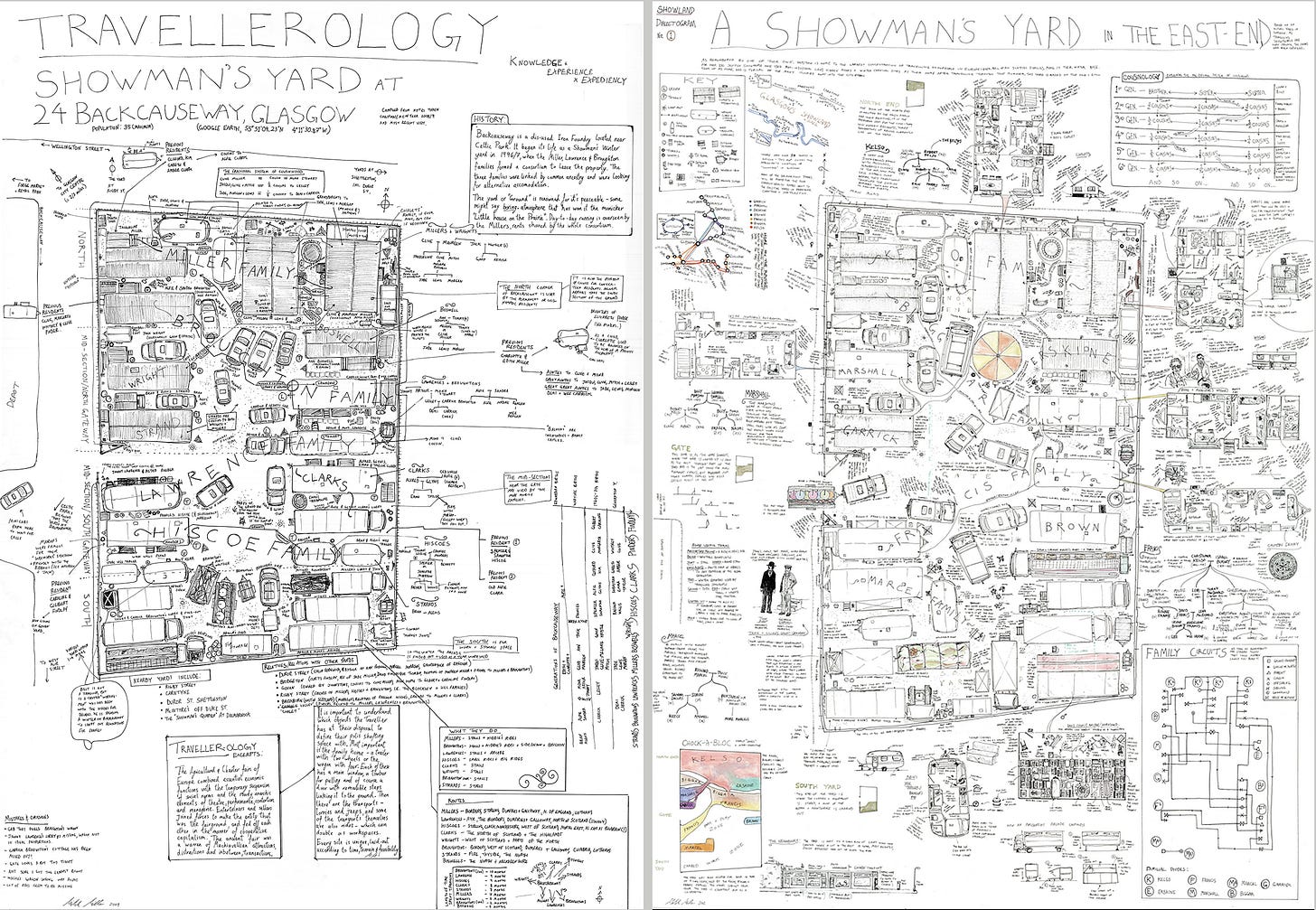

And that is where the dialectogram came in, late in 2009, a vernacular, demotic counterpoint to the authoritative diction of planners’ maps, anthropological schematics, architectural floor plans and other mosaics. A satire of official drawings and the agenda they push. I began the first one by drawing the place where I came from as if I was seeing it from above – the Showman’s Yard where my own parents, siblings and relatives lived. It showed not a here today, gone tomorrow ‘encampment’ (the loaded word local politicos deliberately used to describe them) but what it was – a place that had been there for 11 years, that had its own order, values and culture. My drawing ‘borrowed’ the bird’s-eye view to make a point about what existed in the white spaces of the east end masterplan – the scratchy marks that would never be included in a map of the new Dalmarnock.

*

Titled Travellerology: Showman’s Yard at 24 Backcauseway this first dialectogram was born partly in anger at the way in which Glasgow’s new ‘Games’ End’ was being created out of the old East. Its most immediate inspiration was however, from the sociologist Judith Okely who described a Gypsy camp thus:

When Gypsies choose the layout, they often place the trailers in a circle, with a single entrance. The main windows, usually the towing bar end, face inwards. Every trailer and its occupants can be seen by everyone else.

I had not discovered the pigeon’s-eye view when I read this, but Okely’s piece of diagrammatic thinking is pure street-bird. It begins from above, with the notional, not-quite-closed circle described and then immediately forces us to swoop back down, to the level of the main windows (discernible only when looking at a trailer face on). She ends up placing us in a trailer, appreciating the view from the window itself. Her pigeon-vision poaches the strategic vantage point to better explore and understand what she has learned at ground level. Like a pigeon, she only flies in order to get a better sense of how the streets all fit together, so she can continue to interact with it and crucially, be of it.

Because when the pigeon comes down, it doesn’t just change its focus, it, like Tim Ingold making his way down Mither Tap towards the mosaic wood he saw from the summit, experiences ‘a radically different perception of the world.’ This is the cake – or rather discarded kebab - I want to have and also eat when I make a dialectogram.

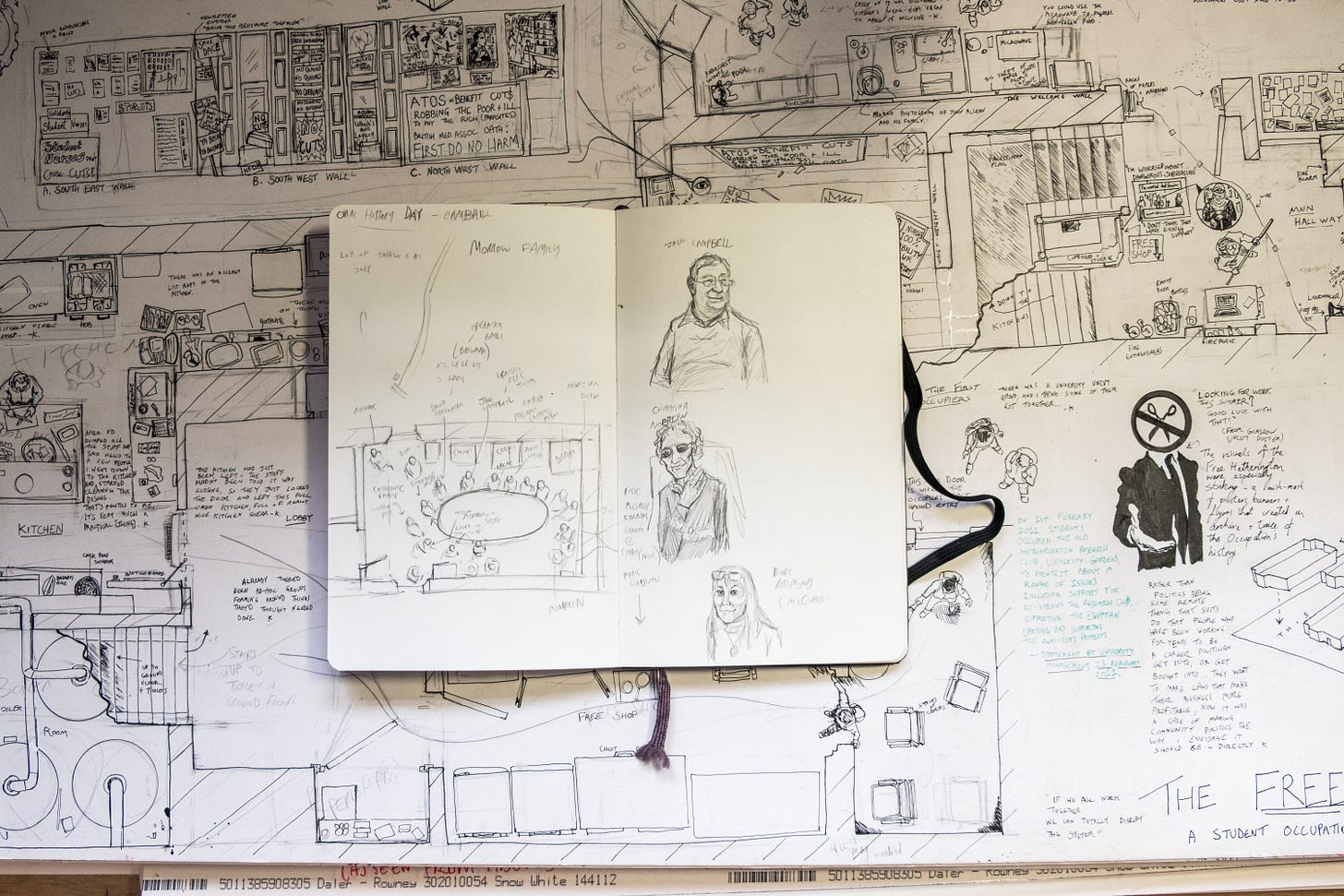

From Travellerology/Backcauseway I went on to produce a series of drawings at the Red Road flats, based on long periods of working with its tenants and employees struggling at all times, to find authentic means to let them speak through the work. The basic idea of the dialectogram was a good start – the tension created by drawing out a floor plan as if from above, then insisting upon explaining that floor plan in terms only attainable from below. The scholar Scott Hames described this to me as a ‘clever way of 'hijacking' third-person/monumental style for first-person knowledge and concrete experience, without relinquishing its authority.’ It flutters down to the tarmac, grabs the discarded chip, then hovers up, looking for the next one…

I like being called clever as much as the next person, but this was also a genuinely useful statement. It scanned fairly well to my then professional position, working on these weird illustrations in the everyday swim of Red Road for a cultural project run by a partnership of such satanic majesties as the Glasgow Housing Association and Glasgow Life (it has to be emphasised that on a personal level the representatives of these organisations were frequently very good people). The contradictions of the political arrangements that made this activity possible are never far from the surface, so that not only was I trying to depict the tactical cleverness of the people of Red Road as they lived in those massive blocks, I had to be equally tactical in the face of various establishment bodies, or to put it another way, political. Call it Realpolitik if you like.

Or perhaps, Pigeonpolitik would be better?

Such are the dangers of stepping out of the studio, but the truth is, I’m in the market for such trouble. There is a pleasure of sorts in this. The contradictions of a project such as Red Road, my recent work for the Hamiltonhill Claypits Local Nature Reserve or the recent commission for the Barvalo exhibition in Marseilles can be a difficult to navigate, but in so doing you have to shed a great deal of pointless baggage: ideological purity is quickly stripped away, but this keeps things interesting and vital and furthermore, possesses certain narcotic benefits. Negotiating between my own values, those of my clients/commissioners and the people I encounter is not fun, per se - but the constant hop from one back foot to another certainly reminds me that I’m still breathing.

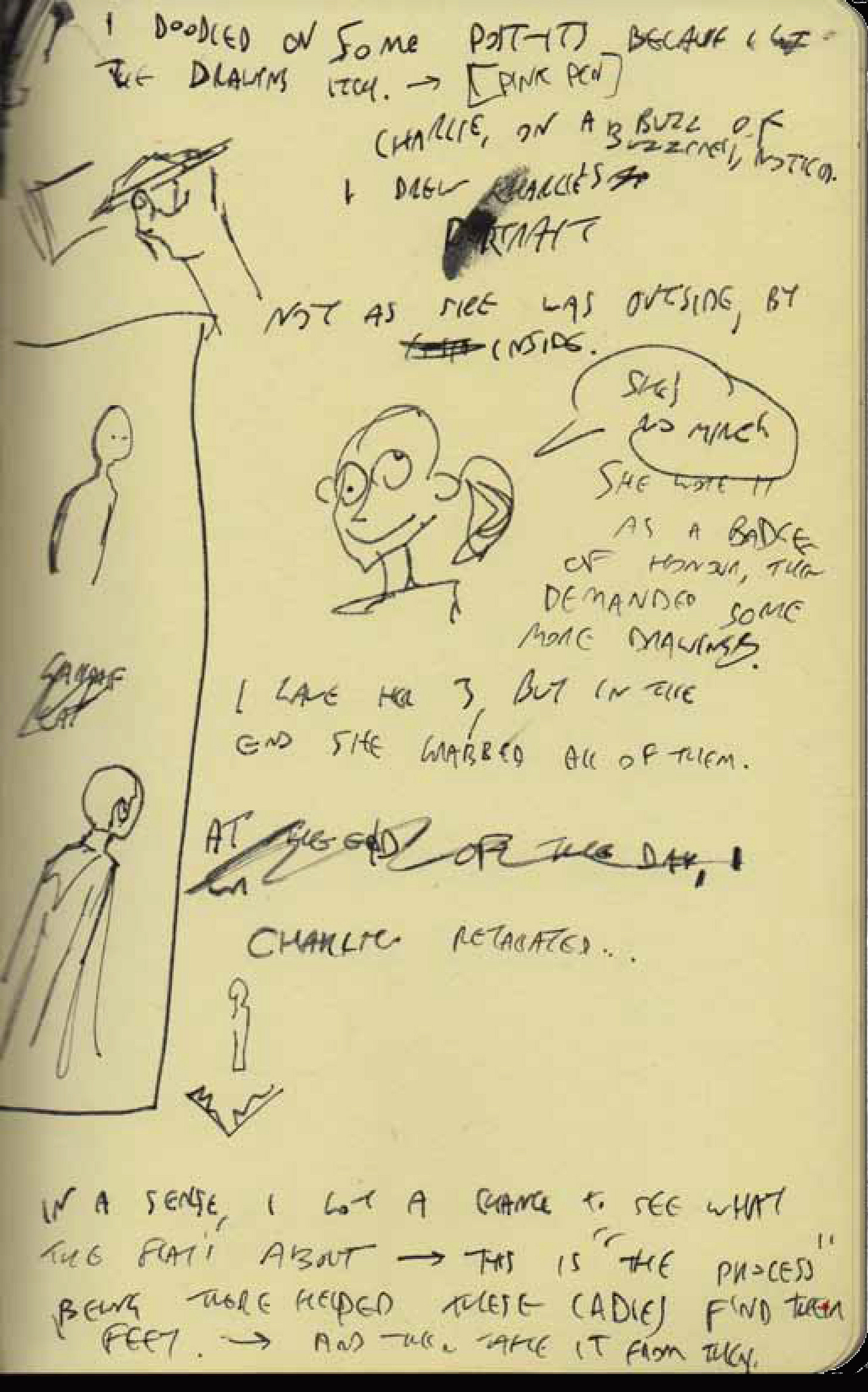

Being out in the field, embracing a community that is not mine, but finding ways to come to terms with, has pleasures of its own, a succession of small but important triumphs. The cultural critic Elizabeth Sandifer calls this ‘collectivist hedonism’, squeezing joy out of the world less from what we can extract from it individually, than through how we relate to each other - on-going existential inquiry through laughter and gossip. For Okely and myself you could say it’s a ‘hedonism of the field’ where we embrace lives that are either unlike ours, or at some sort of remove. With every dialectogram project I run the risk of being changed, every time I pick up my sketchbook, chap on a door, hunker down by a playground fire pit, or gratefully accept a cup of tea. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t enjoy it, and the possibilities of how it will affect me.

Since that first satire, the dialectogram has become a participatory thing – and I do mean thing. I am not a fine artist; I have no training in that tradition and am fortunate that bodies such as MoMA, or Collective were happy to work with interlopers such as myself. I am an illustrator, which means I straddle the great aesthetic tribes of art and design – that is, steal merrily from both. I draw inspiration (if you’ll pardon the pun) in equal measure, from Mikhail Bakhtin’s dialogic aesthetic found in contemporary art, or Bruno Latour and Pelle Ehn’s notion of the ‘Thing’ as an assembly around (and about) material.

Which means…? Well, let’s start with the material, going from the large to the small scale– a Ballroom, a Town Hall, a Steeple, then its constitutional fixtures and features, slabs of concrete scatters of gravel, carpets that suck at your sole, water coursing through a canal and then finally to the last level, of objects - clinking mugs of tea or sloshing pints of Tennents. This is the material I- or rather we – are concerned with finding some sort of way to talk about. And that brings in other material from outside to assemble around– the big white mount board I would draw upon and the oral accounts of the participants who agreed to take part. We discuss their lives, what the place meant to them, but also what we could illustrate about their place, and how. This means asking them to imagine it as if from above, and then anchor that in their grounded experience. It asks them to think a bit like me, just as I was learning to think a bit like them. It asks them to be pigeons.

Done right, this method can enable a group of people to rethink and illustrate the complex relationships and problems of their place. The drawing itself, generally shown to them many times during its long, tortuous road to something like completion, becomes a sort of place where we could build new relationships between each other, remember old stories, create new ones, discuss things that were not usually discussed but left implicit.

What I am trying to get across is that the dialectogram is not just the drawing but a kind of behaviour, a state of mind through which I participate in these contexts, whether its fun-days, baton-relay events, going backstage at gigs, planting trees or games of hidey. I draw pictures to order, I give (often distinctly idiosyncratic) walking tours that encourage those who join it to see a given space in my skew-whiff fashion. I try to create an atmosphere where we could all acquire pigeon-vision. Participants do their own fieldwork on my turf too– they visit my studio, see my works in progress, even share my arch-comic geekery. We get to know each other. We flock together. We make dialectograms.